Upper Body Blast: Get a Bigger Back, Shoulders and Arms

Close-grip pull-ups (or chins) were probably forced on you in gym class, perhaps by an overweight PE teacher (who had not done pull-ups in many years). If this was the case, you may not have developed much affection for this exercise. However, it turns out that this old-school exercise is really a very good tool for blitzing most of the muscles of the middle and upper back, shoulders, chest and arms.1,2 It also turns out that close-grip chins are great to use if you are traveling and not near a gym, and also as an addition to your back- or arm-training day.

Muscle Structure and Function

Many muscles are recruited to accomplish close-grip pull-ups, which makes it a difficult but extremely productive exercise. This includes everything from the intrinsic muscles of the hand to grip the bar, to the forearm and especially the upper arm muscles that help in the pull upwards, and the deltoid and upper back muscles to continue the pull-up.

The latissimus dorsi muscle is a major upper back muscle that is activated by close-grip pull-ups.1 This muscle connects the vertebrae in the thorax and lumbar regions and the iliac crest of the hip bone, to the humerus bone of the upper arm near the shoulder.3 The muscle fibers of the latissimus dorsi muscle adduct the humerus (bring the arm toward the center of the body), and extend the humerus (pulls the arm backward) to pull the body upward toward the bar. The close-grip pull-up keeps the humerus in an adducted position. The upper fibers of the latissimus dorsi muscle are most completely activated when the hands begin above shoulder height and they are pulled toward the armpits (axilla), during the pull-up exercise.

The teres major muscle begins on the inferior angle of the scapula (shoulder blade), and it attaches to the humerus bone of the upper arm. It assists in arm extension, and adduction of the arm at the shoulder joint when the arms are over the head in close-grip pull-ups.3 The short head of the biceps brachii muscle begins on the front part of the scapula bone.4 The long head of the biceps brachii muscle attaches on the scapula near the shoulder joint. The long head sits on the lateral part of the arm, and its fibers mesh with the short head on the medial side of the arm to insert into the bicipital tendon, which attaches to the radius bone of the forearm. Both heads of the biceps flex the elbow joint.4

The brachialis muscle is also a major elbow flexor.4 It begins on the distal half of the humerus and it inserts on the ulna bone of the forearm. Even the pectoralis major muscle of the chest is activated in close-grip pull-ups.1 The sternocostal head of the pectoralis runs from the manubrium (the top portion of the sternum or “breast bone”), and the upper six ribs and converges near the head of the humerus.4 The pectoralis major muscle adducts the humerus in the close-grip position. It is most active at the beginning of the pull-ups, and it has less of a role as the chest is pulled close to the bar.

The upper fibers of the large trapezius of the upper back attach along the posterior base of the skull and the cervical vertebrae of the neck. These fibers attach to the lateral part of the clavicle (collar bone) and along the spine of the scapula. They pull the clavicle upward in the pull-up. The middle fibers of this muscle begin on the upper thoracic vertebrae, and then run to the spine of the scapula. They pull the scapula toward the vertebrae at the top of the pull-up.5

Close-Grip Pull-Ups

If you cannot do bodyweight pull-ups, use an assisted pull-up machine, as this will allow you to get the benefit from the exercise without requiring you to initially have the strength to pull up your entire bodyweight. After a couple of weeks, you will be able to reduce the amount of weight on the assisted machine, and in a few months you will be ready to tackle the exercise without any additional resistance on the assistant machine.

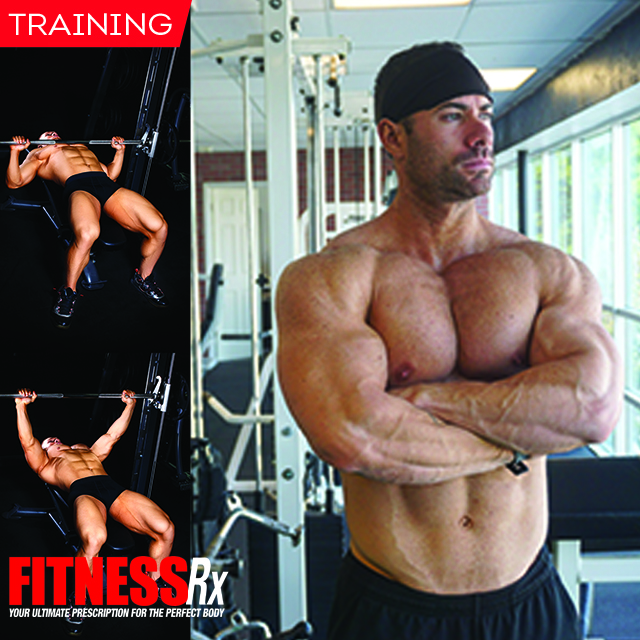

1. Follow the instructions for your assisted machine pull-ups for setup (kneel or stand on the platform as appropriate) and select desired weight. If you are not using the assist machine, step up on a box that will allow you to grab a pull-up bar.

2. Take a narrow grip4 (shoulder width or slightly narrower) on the bar overhead, just above your head. The hands should be pronated (palms facing away from your face).

3. Pull yourself up (flex the elbows and extend the arms) until the bar is adjacent to the upper part of the chest (just above the chin). Attempt to get your body as high as possible to ensure a complete contraction of the upper and intermediate back muscles (i.e., trapezius, and small scapular muscles) and the elbow flexors (biceps and brachialis).

4. Slowly (3-5 seconds) lower yourself until your arms, upper back and chest are completely stretched at the bottom position. Start upward and repeat the sequence to finish the set.

The pull upward extends the humerus bone and activates the latissimus dorsi, teres major, part of the pectoralis, trapezius and deltoid muscles.1,2 The elbows, however, must flex so the biceps brachii and brachailis muscles are strongly activated.3,4

Don’t get bummed if at first, you find it difficult to do the pull-ups without some assistance. With some consistent effort and time invested into the training program, you will be able to reduce the assistance and pull your body up multiple times and without any help. The hanging position on the close-grip pull-up causes a traction gravitational load on the spine2 that safely carves out a strong, hard-as-granite look to your upper body. Not a bad result for such a basic old-school exercise.

References:

1. Youdas JW, Amundson CL, Cicero KS et al: Surface electromyographic activation patterns and elbow joint motion during a pull-up, chin-up, or perfect-pullup rotational exercise. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:3404-3414.

2. McGill SM, Cannon J, Andersen JT: Muscle activity and spine load during pulling exercises: influence of stable and labile contact surfaces and technique coaching. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2014;24:652-665.

3. Tucker WS, Bruenger AJ, Doster CM et al: Scapular muscle activity in overhead and nonoverhead athletes during closed chain exercises. Clin J Sport Med 2011;21:405-410.

4. Moore, K.L. Clinically oriented Anatomy. Third edition. Baltimore, Williams & Williams, 501-553, 1992.

5. Signorile JF, Zink AJ and Szwed SP. A comparative electromyographical investigation of muscle utilization patterns using various hand positions during the lat pull-down. J Strength Cond Res 16: 539-546, 2002.