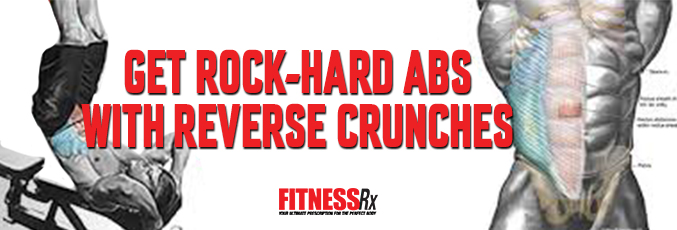

Get Rock-Hard Abs With Reverse Crunches

If you are interested in stepping into a rock-hard abdomen from top to bottom, you should consider adding a few sets of reverse crunches to your routine.

The region of your lower abdomen, just below the navel, is very hard to isolate and even more difficult to harden. Regular crunches and incline sit-ups are pretty typical exercises for the upper abdomen, but these exercises do not provide much direct stimulation for the lower part of the abdomen. Optimal activation of the lower abdomen demands that the front (anterior) part of the pelvic bones rotate slightly upward. This is achieved in the reverse crunch. The reverse crunch is so effective, because it shortens the fibers of the lower abdomen, and tilts the pelvis upward at the beginning of each lift. Furthermore, this exercise maintains near constant tension in these muscle fibers throughout the exercise. If you are interested in stepping into a rock-hard abdomen from top to bottom, you should consider adding a few sets of reverse crunches to your routine.

Muscles Used

The rectus abdominus is a long abdominal muscle that is made up a series of short fibers that are stacked vertically. The linea alba is a thin tendon in the middle of the abdominal wall that divides the rectus abdominis into two halves. When the rectus abdominis is tensed, the fibers bulge between the horizontally placed tendons that connect to the linea alba. The upper part of the rectus abdominus helps to move the head and torso closer to the hips and legs. The lower part of the rectus abdominis is attached to the upper area of the pelvic bones and pulls the pelvis, and tilts, or rotates it upward. Reverse crunches target the lower two horizontal rows of rectus abdominus muscle fibers.

Both the external and internal oblique muscles on the sides of the abdomen are activated by reverse crunches – but in doing so, they function as torso stabilizers. Bundles of fibers from the external oblique muscle run from medial to lateral on the lower ribs. The external oblique fibers attach on the iliac bones of the pelvis, the hip structure and the linea alba. Together, both left and right sides of the external oblique muscles flex the trunk so that the thighs move toward the head during the reverse crunch exercise.

The internal oblique muscle is deep to the external oblique muscle. It attaches to a sheet of connective tissue in the lower back, called the thoracolumbar fascia. Its fibers run around the side of the trunk at right angles to the external oblique muscle and it anchors to the lowest three or four ribs. Similar to the external oblique muscle, the internal oblique flexes the trunk at the waist and lifts the thighs toward the head when the head is stationary on the bench.

The iliopsoas muscle is a deep muscle that is located along the front of the lower spine and pelvis. This muscle is really made from the psoas and iliacus muscles. The psoas muscle is located adjacent to the lumbar vertebrae, and the iliacus is positioned along the iliac bone of the anterior pelvis structure. These two muscles come together to form one muscle, the iliopsoas, which attaches via a tendon to the head region of the femur bone. This muscle is a powerful hip flexor, and helps to bring the knees toward the chest; however, it acts as a hip stabilizer in reverse crunches.

Reverse Crunches

Instead of crunching your head and torso toward your thighs as in a normal crunch, in the reverse crunch, you will raise your thighs, hips/pelvis, and legs toward your face.

1. Flex your knees and hips so that your thighs become perpendicular to floor.

2. Pull (curl) your pelvis toward your head. This will only result in a few degrees of movement. Next, lift your pelvis and lower back upward.

3. Move your knees toward your head by lifting the lower back from the bench. Try to focus on feeling your lower abdominal fibers shorten and tighten as you lift your hips and legs upward.

4. With your knees flexed and your thighs parallel to the floor, return your legs and hips slowly toward the starting position.

5. At the point that your sacrum and coccyx (tailbone) of your posterior pelvis makes contact with the bench, immediately begin the next rep upward.

6. Repeat the sequence for 20-25 reps in a slow and deliberate fashion. This should take about 2 seconds to lift the thighs and 2-3 seconds to come down. Work up to three sets of this exercise.

When this reverse crunch becomes too easy, you should do the exercise on a decline bench. This is done in the same way as the flat bench, but your head should be at the high end of the decline bench and your feet start at the low end of the bench. The angle will increase the effort that you need to move your legs upward.

Try to avoid holding your breath during the reverse crunch, because this would greatly increase your intra-abdominal pressure and this prevents your rectus abdominus fibers from shortening fully when you lift your legs upward. Instead, you should exhale as you are crunching your feet toward your head.

The reverse crunch is an exercise with a small range of motion, but it delivers big results. The fibers in your lower abdominal wall should feel as though they have been through a meat grinder at the end of your sets, but this is only temporary. The transformation will be more long-term and the results will be worth the effort. Not only will reverse crunches transform your abdomen, they also will help to ward off abdominal and groin injuries, which unfortunately, are problems that are encountered by athletes across a wide variety of sports. Reverse crunches will transform your lower abdomen into a solid steel-plated column that will not only look great, but keep you injury-free. This is not a traditional abdominal exercise, but it is one that will to get your abs in outstanding shape.

References:

Agur A., M. R., K.L. Moore, A.M. Agur. Essential Clinical Anatomy by Third Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, April 2006 ISBN: 078176274X.

Atkins JM, Taylor JC and Kane SF. Acute and overuse injuries of the abdomen and groin in athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep, 9: 115-120, 2010.

Gidaris, D, Hatzitaki, V, & Mandroukas, K (2009). Spinal flexibility affects range of trunk flexion during performance of a maximum voluntary trunk curl-up. J Strength Cond Res, 23, 170-176.

Parfrey, KC, Docherty, D, Workman, RC, & Behm, DG (2008). The effects of different sit- and curl-up positions on activation of abdominal and hip flexor musculature. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab, 33, 888-895.

Teyhen, DS, Williamson, JN, Carlson, NH, Suttles, ST, O’Laughlin, SJ, Whittaker, JL, Goffar, SL, & Childs, JD (2009). Ultrasound characteristics of the deep abdominal muscles during the active straight-leg raise test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 90, 761-767.

Workman, JC, Docherty, D, Parfrey, KC, & Behm, DG (2008). Influence of pelvis position on the activation of abdominal and hip flexor muscles. J Strength Cond Res, 22, 1563-1569.

Youdas JW, Guck BR, Hebrink RC, Rugotzke JD, Madson TJ and Hollman JH. An electromyographic analysis of the Ab-Slide exercise, abdominal crunch, supine double-leg thrust, and side-bridge in healthy young adults: implications for rehabilitation professionals. J Strength Cond Res, 22: 1939-1946, 2008.